The methodology yields this ranking.

Top 20

1. Harvard

2. Columbia

3. MIT

3. Stanford

5. Duke

6. Yale

7. Caltech

8. Penn

9. Princeton

10. Cornell

11. Brown

11. UChicago

11. WashU

14. Rice

15. Northwestern

15. USC

17. Dartmouth

17. Johns Hopkins

19. Emory

20. Carnegie Mellon

top 5 LACs:

22. Williams

23. Amherst

26. Pomona

28. Wellesley

30. Swarthmore

top 5 public universities:

25. UCLA

27. UM Ann Arbor

33. UNC Chapel Hill

40. UC Berkeley

43. Purdue

USC is ranked appropriately as is UCLA. Keep in mind this is a ranking of the college. USC's students are really good. They are extroverts, articulate and "fast on their feet". UCLA featured many more students who crammed for exams and excelled at this "ancient art" but lacked creativity and versatility.

-

Given the recent discussion about women's opportunities in Silicon Valley and in academic economics, I took a look at my own record. I have published six books. I wrote 4 by myself and 2 with co-authors. Both of my co-authors (Dora Costa) and (Siqi Zheng) are women.

In terms of journal articles, out of my roughly 130 publications --- I see that I have published 40 papers featuring at least 1 female co-author and I have worked with 10 different women on these papers.

I have written 30 papers that each have at least 100 Google Scholar cites. 11 of these papers feature at least 1 female co-author.

REPEC could add diversity criteria for ranking economists. It wasn't my intent to rise on this margin but I do like what I see.

-

The USC Daily Trojan has published an article that I like. I moved from UCLA to USC because I saw the private university's momentum and ambition. My department's goal is to be as good as our football team. The University aspires to be Stanford. That's a good goal and we are working to achieve this. The University of Chicago's economics department has been rewarded for building up a very strong major. Their Deans have invested heavily in that department. I hope (and expect) a similar dynamic to play out at USC.

-

Erin Mansur and I have a well cited 2013 JPUBE paper documenting that energy intensive firms cluster where energy prices are low (the paper has several other ideas!). Siqi Zheng, Jianfeng Wu and Weizeng Sun and I have a 2017 JUE paper studying China's industrial parks. In these parks, land, capital and electricity is often subsidized. The NY Times reports today on an obvious synergy of these two papers. Energy intensive bitcoin companies in China are locating in cheap energy places and mining the coins. This produces cash and carbon because in places with cheap power in China, the power is generated by coal.

This reminds me of a story. When my son was age 10, he would keep his computer on at night to mine bitcoins. He figured out that I pay his electricity bill (his costs) but that he would keep the revenue on any bitcoins he mined. He thought that he had a "money pump" until I reminded him that he will inherit all of our wealth and that the overall profitability of his operations was negative. The same logic applies to China's firms today if you substitute the words President Xi for Matthew Kahn.

Environmental economists haven't done enough work on "perverse subsidies". As governments keep gas prices and fossil fuel energy prices low, how does this affect the scale, composition and technique of industry? We have much more work on the vehicle fleet on this topic but not enough about the industrial and commercial sectors.

-

As I read the NYT and WSJ, I see similar stories that the Big Data Smart Phone era reduced the suffering caused by Hurricanes Harvey and Irma as people used their phones to "trade with each other" such that private first responders saved many people. Permit me to ask an economics question, should the suppliers of rescue services be compensated?

They will receive praise but should they receive money? Uber drivers are paid. What is the difference between Uber and disaster relief?

Titmus vs. Hayek

Who is the Great Titmus? He argued back in 1970 that paying for stuff such as blood leads suppliers to recoil and supply less. What would Hayek say?

If an App programmer created a disaster market place "Uber", would more people be saved or would fewer? How would surge pricing work? Who should be allocated the scarce rescue services during a crisis? If the supply curve is elastic, will more first responders be available during the surge? Do the potential first responders place themselves at risk during a disaster by sticking around rather than evacuating?

Do markets work in the middle of a crisis? -

On my twitter feed today, I stumbled across this very interesting (and depressing) post by Claudia Sahm. MIT's great Peter Temin wrote this piece about "culture" 20 years ago. He discusses Alberto Bisin's early work on culture. Here is a great Vox EU piece by Bisin on culture that poses some intellectual puzzles for comparative economists.

Dr. Sahm's piece raises a fascinating question; does academic economics have a bad culture? The goal of academic economics is to build up knowledge to provide a scientific method for judging the efficiency and equity consequences of different public policies and to train the next generation of economists. Does our culture further this goal? If not, how did we get into this equilibrium and if we are in a "bad equilibrium" where we are losing talent because of our bad culture, how do we switch equilibrium?

To even begin to think about this question requires delving into a tough-counter factual; who would enter our field (selection) and how would senior incumbents allocate their time and effort (treatment) if we had a different culture? Would junior incumbents in our field achieve more if we had a "better culture"?

Given that each economist has only 24 hours in a day and is competing for scarce resources such as slots at universities, great students, grants, journal pages, attention from the media, attention from our spouses, friends and children and parents, what should be our "rules of engagement"?

I remember reading Dubner of Freakonomics saying that economics is "cut throat". While we celebrate perfect competition in Econ 101, do we engage in perfect competition (pun intended)? Have you met economists who are charming in public but talk behind the back of colleagues? Of course. The anonymous web has simply taken those past private conversations and made them public so that everybody is next to the watercooler as the big talker talks. Perhaps the Web has also created a "learning effect" as others learn the dark art of bad mouthing other people.

In a "rat race", how much of one's progress is due to rising by merit vs. tearing down others?

In the TV Show the West Wing, a perfect President (who had a Nobel Prize in Economics!) led a organized respectful team. Most economics departments do not have this same feel. Younger faculty face tension over the tenure process. The senior faculty must choose whether to stay in the game or devote more time to consulting and leisure. Graduate students must choose who to work with and what problems to work on.

At USC Economics, we are thinking about what are a set of "rules of the game" so that PHD students, junior faculty and senior faculty all learn from showing up to the department. Mutual respect is a "two way street". Tom Sargent said that we are all students but differ with respect to our vintages.

The challenge in economics is "directed search". If a senior faculty member believes that he is unlikely to learn from interacting with a PHD student from a LRM (ha!) then he will focus his attention on the HRM PHD student. Given our finite time, this search strategy may be "individually rational" but it begins to create monopoly power that is re-enforced as that HRM PHD student takes a job at a MRM Assistant Professor job and is named to the NBER. Small differences in initial conditions do matter in a world of finite time and attention. If we add to this sexism and racism then this exacerbates the challenge.

I HAVE UPDATED this part of the blog post.

So yes, culture matters. I don't know what tax or subsidy to introduce here to rectify my market's failure. I don't know how far the CE is from the Pareto Optimum. I have benefited from the status quo rules. I don't know how much I have benefited from them.

Mutual respect takes time to implement. It is easy to state that we should abide by this but there are thousands of young PHD students. How do we "sort them" efficiently?

Relative to other fields, our culture has a few clear differences;

1. Researchers are very tough on each other in public seminars (the "Chicago seminar" style). At UCLA History seminars, the speaker reads from notes and at the end of the hour, polite listeners then ask questions.

2. People do not read each other's papers so the ability to speak and argue is even more important. Since people do not read, an endorsement from a very important person carries much weight.

Final Thoughts;

Is part of the problem that academic economics is a "non-profit sector"? Google as a for profit firm has the right incentives to have a good culture because shareholders will earn a higher rate of return if the good culture at Google allows this firm to hire and retain skilled workers at a relative low salary.

Since senior faculty have residual control of departments but do not have "equity" (i.e stock shares) in economics departments, do we have strong incentives to improve "the culture"? In economics, departments such as Berkeley and MIT have been ranked quite high because they have been known to have a great culture of hiring strong juniors and mentoring them so that they become tenured some then leave a Berkeley (think of Chetty while others remain think of Saez). Other schools such as Columbia in the 1990s suffered because they had "bad cultures".

So, this suggests that competition between schools and a desire to rise in the rankings should encourage departments to "compete on culture". At USC , we are trying to implement this but this is easier said than done.

-

Sep9

A Structural Discrete Choice Model of Amazon's HQ Decision: A Blog Post (not an Econometrica!)

Dating at least back to Dennis Carlton's 1983 RESTAT paper, economists have written down an indirect profit equation that measures a given firm's profit if it locates in a given geographic area such as Chicago or Nashville. Suppose there are 87 of these different locations. A profit maximizing firm will estimate its profit if it opens its headquarters in each of these locations and then choose the location based on the maximum value across these 87 numbers.

Why would a decision maker such as Amazon earn different profit if it builds a headquarters in different locations?

1. the rent it pays per square foot will vary across locations.

2. the tax breaks it receives will vary across locations

3. the human capital it can hire will require different "combat pay" in different locations. In a beautiful city, Amazon can lure and retain talent at a lower wage than if it chooses to locate its headquarters in a humid, dangerous place.

4. If Amazon is energy intensive or water intensive in producing output, it will think through what its operating costs will be from being headquartered at each location.

5. If the executives have families, the executives will think about what city specific schools their kids will attend, what city specific jobs and activities their spouses will participate in (the co-location problem), they will think about what city specific restaurants and country clubs they will participate in (the consumer city). The executives will care about climate and quality of life because leisure time will mainly be consumed in the hq city. Bottom line, in a nicer city --- Amazon can pay less and retain and recruit talent. The area's attributes are part of the total compensation package. Sherwin Rosen taught me this 30 years and this is the heart of my quality of life research (see this and this).

If the firm expects to spend at least 30 years at this location, it must not only collect information on #1 to #5 today but also form an expectation of each of these attributes over the next 30 years. The econometrician studying this firm must form a model of the firm's expectations of how these atributes will evolve over time. If the econometrician is lazy and assumes that the firm believes that cities never change then the econometrician will mis-specify what information the decision maker actually used. This is why the rational expectations approach became so popular because it provided an intellectual justification for the "symmetry" between the decision maker and the researcher studying the decision maker. For example, if Amazon believes that climate change will make Nashville 120 degrees in summer by the year 2023 but the econometrician assumes that Nashville's average temperature each summer never changes, the econometrician will over-estimate the probability that Amazon chooses to place its HQ in Nashville.

This brief sketch highlights the challenge for an econometrician who seeks to quantify the relative importance of these 5 factors in determining a billion dollar firm's choice of place.

Now, if the econometrician has the data on what is each firm's set of "finalist"locations (i.e chicago, Nashville), and observes which location each firm chooses for its new HQ and if the econometrician observes a vector of city attributes (see #1 to #5 above), the researcher can estimate a MacFadden conditional discrete choice model to recover estimates of the marginal coefficients on attributes #1 to #5. This is a revealed preference approach as the econometrician seeks to recover the decision maker's priority list (i.e. is #1 more important than #5 in determining locational choice?).

The econometrician would face the challenge that there aren't that many Amazons choosing where to go. A referee might also say that there is so much heterogeneity that you can't pool different companies together because every company has different weights that it places on factors #1-#5 above. In this case, the ambitious econometrician could not estimate this statistical model.

But, if you can't estimate this model; then we will never know if Chicago "overpays" to recruit Amazon. Why? The key counter-factual is whether in a probabilistic sense; would Amazon have still been likely to have chosen Chicago in the absence of great tax incentives? If the answer is "yes", then Chicago overpaid. In this case, Amazon wasn't at the Margin. But, we will never know this if we don't estimate the model above that provides a quantitative metric of how leading companies tradeoff the factors listed above.

-

Amazon will soon choose a new location for building its 2nd headquarters. Chicago may be chosen. The winning city will receive an influx of high paying jobs and this will boost housing prices, human capital, restaurant demand and tax revenues. Cities are competing by offering tax breaks. Will Winner's Curse arise as cities over-pay?

Now let me turn to climate change adaptation. Critics of my free market adaptation work sometimes argue that a large percentage of the population have the wrong beliefs such that these climate deniers under-estimate the risks that a geographic area such as Miami will face in the future. I do not deny that there are climate deniers. In recent work, I have studied how their existence affects induced innovation.

But, these critics ignore general equilibrium effects. I believe that both major employers such as Amazon and the insurance industry are the "adults in the room". Amazon will not open a new durable and expensive headquarters in a location that climate change will destroy. Such firms will be more likely to choose a location with good fundamentals and where the urban leaders are upgrading the infrastructure to protect it from future threats. A mayor who is a climate denier but seeks to attract major employers will cater to such employers because the mayor needs a major employment center. People follow jobs! So, even in an economy featuring "deniers" and political leaders who are "deniers", a mayor who wants to attract new high paying jobs to her city has an incentive to invest in risk mitigation. This topic has not been explored by professional economists.

For more on my ideas about the future of insurance in protecting us from climate change, read my recent HBR piece.

-

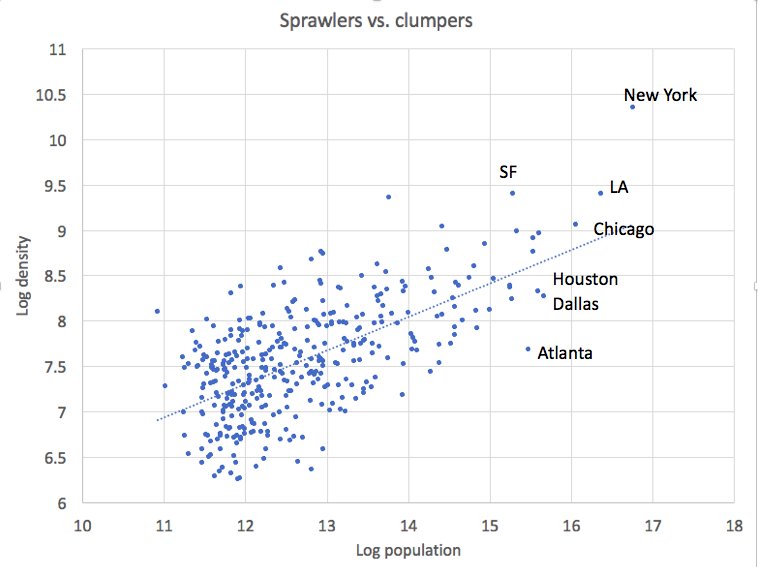

Dr Krugman tweeted this. I am not smart enough to completely see his thoughts embodied in these 140 characters but I am going to try because this raises a fundamental issue in urban economics. Below, I reproduce his cross-U.S city graph of log population density as a function of log population. I believe that Dr. K wants you to see that "smart growth" progressive cities are above the regression line while sprawling cities such as Houston, Dallas and Atlanta are below the regression line. So what?

A city such as SF (San Fran) has a higher population density than its population would on average predict that it should. Such a city is "economizing" on land as people live in multifamily housing rather than sprawl.

But, Dr. K is ignoring prices. The reason why people live at higher density in SF , LA and NYC is that land per acre is so expensive. When you live in a high rise , you are sharing space with others and economizing on this scarce asset. Where land is cheaper in Atlanta, Dallas and Houston, people consume more of it.

Now, let me say something smarter. A good economist would ask, is Atlanta land cheap because of supply or demand? In English, is Atlanta undesirable and thus demand is low and this yields low land prices or is Atlanta land cheap because there are fewer zoning restrictions and this shifts out the supply curve or makes it more elastic? How does Dr. K. plan to answer this?

Second, suppose that in a place such as Houston one can buy a nice $500,000 home but one does have to face the Houston humidity and the rising risk of Hurricane Harvey risk. Does this still yield greater expected utility than living in a studio with 4 other guys in NYC for the same rent? What is the good life? What if we have different conceptions of the good life? In a world where people differ (diversity) why can't we be free to choose? We explore some of these themes in the following papers available here and here. If people have different risk aversion parameters then some may choose cheap, humid (and increasingly risky) Houston over more expensive smaller housing on higher ground. Are they "free to choose" to make this choice? Now I recognize that if they receive federal bailouts when disasters do occur that this encourages moral hazard effects and this is ugly and needs to be changed.

Dr. Krugman's tweet raises deep issues regarding the gains to a household from living in its own single detached house (with its own land) versus sharing with strangers. In a world of consumer sovereignty, economists can point out the social costs associated with owning a lot but we can't question where that core private benefit from seeking that lot comes from. As I recall, when Dr. K taught at MIT -- -he had a very nice single family home close to Harvard (I lived in a multifamily building nearby).

Let me end with a real PHD economics question. Dr. Krugman has a clark medal and a nobel prize. I have neither. A real home run paper in this paper will disentangle whether supply side restrictions on housing (i.e zoning) make an area more desirable (i.e shift out demand). Think of Paris or NYC. While Glaeser and Gyourko emphasize the costs of zoning (see the post above), what are the benefits of zoning? In an age of climate change, would Houston be how much resilient of a city if it has zoning? How much more expensive would that $500,000 house I quoted above be? Would it have been built? These are the real questions we must grapple with.

So, if Houston was built at NYC density --- would the land that is currently developed with single family homes be wetlands? If these wetlands did exist, how much would flood risk decline by and how much do the Houston residents (who would be living in multifamily housing) value this? Versus do they prefer to live in cheap , large single family homes that face increased flood risk? Isn't this the core question? In a world where people have different preferences and there are no free lunches, could different urban forms emerge and we let Tiebout sorting playout? Now again, if federal $ is used to bailout risky places then this logic is weakened but perhaps it is now time to name Milton Friedman as the head of FEMA ( I call for this in my 2010 Climatopolis book).