I should send Ed Mills two copies of the 2008 Chinese Translation of my Green Cities book. Maybe he would like this one more than the original english version? I still like my book a lot. My co-author Siqi Zheng helped make this translation happen. I'm grateful to her for her help.

If you bothered reading my last blog entry, I wanted to expand it a little. As you might remember, I briefly listed what I think are the 6 biggest issues in environmental economics. I would encourage all young environmental scholars to be working on these topics!

Let me return to endogenous technological innovation. Intuitively, if the people of Berkeley all install solar panels do firms in this industry enjoy large learning by doing effects? Does their cost of production decline as a function of cumulative experience? Why does this matter? If learning by doing effects are large, then we can be optimistic that a big green demand push today (either due to government subsidies or population expressed environmentalism) will help to lower the price and raise the quality of future green products. Just as the Pentium computer is better than the old 386 PC, learning by doing would mean that future solar panels will be of higher quality than products today because the producers gained experience. The devil here is how you measure these learning gains.

A second source of endogenous technological innovation is the induced innovation hypothesis. As the price of inputs (such as energy costs) go up, which firms are nimble enough to change their production processes to minimize their consumption of the now costly inputs such as oil? We know that Southwest Airlines has done well recently in terms of profitability because it hedged gasoline prices and bet that gas prices would go up and they locked in to purchase gas at a lower price but in the medium term if they are betting that gas prices will stay high are they ordering air planes that are more fuel efficient? What strategies are they embracing to deal with expensive natural resources in the short run, medium term and long run?

I can see how a business professor can write nice single company case studies here. The challenge would be how you pool these case studies to be able to conduct a statistical analysis of how heterogeneous firms respond to expectations of rising natural resource prices.

-

I have returned from 4 days and nights at the NBER Summer Institute. The highlights included Marty Weitzman's talk on "fat tails" at the Environmental Meetings and the dinner celebrating Marty Feldstein's major contributions as President of the NBER for the last 30 years. It does amaze me that Dr. Feldstein took over the bureau at the age of 38. If you want to see this year's conference program go to www.nber.org/~confer.

There were over 100 people attending the environmental meetings. While I can't say that every paper presented was great, each of them highlighted different exciting things going on in environmental economics. My friend Matt Kotchen asked over lunch what I thought were the top issues in environmental economics these days. I sat down and thought about this and here are my top 5. They are not in order;

1. How large are learning by doing effects for renewable energy technologies such as wind and solar?

2. How much damage will we suffer from climate change if average world temperature increases by T degrees? Where T takes on the values 1, 2, 5, 10, 30 c? Marty Weitzman's point is that each of these states of the world have non-zero probability of taking place. So, how much damage and who suffers the damage from each of extreme weather events?

3. When carbon pricing is introduced, which industries, nations and households will bear the incidence of this taxation?

4. Are consumers indifferent between "natural capital" and man-made engineered products? So for example, think of gentically modified foods versus organic foods -- are you indifferent? Is there any price differential such that you would be indifferent or do you view the GMO as "frankenfoods" that you wouldn't touch?

5. What are the causes of environmentalism? When people are environmentalists how does this affect their answer to #4 above?

6. Building on #5, we need structural consumer demand estimates of the willingness to pay for "green" products (think of the Prius) or tofu and how these estimates vary by population demographics and ideology. -

It's Our Earth, Now What Do We Do With It?

By EDWARD GLAESER, Special to the Sun | July 18, 2008

http://www.nysun.com/arts/its-our-earth-now-what-do-we-do-with-it/82183/

Political movements are often built on literary foundations. Abolitionism owed much to "Uncle Tom's Cabin." Progressivism had Upton Sinclair and Ida Tarbell. Books, fiction or not, have the power to convince us impressionable readers that we face dire threats, such as unclean meat or pesticides. Political entrepreneurs, promising to protect us from those threats, can then work on the fertile ground of our fears.

The environmental movement has been very successful at making America afraid. Forty-five years ago, Rachel Carson's "Silent Spring" convinced the public that DDT was a great threat to our ecosystem; more recently, Vice President Gore's "An Inconvenient Truth" created widespread alarm about global warming. In 1968, Paul Ehrlich's "The Population Bomb" terrified millions with its claim that humans had overtaxed the environment and that "in the 1970s and 1980s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now."

Inconveniently for Mr. Ehrlich, but luckily for the rest of us, his prediction did not come true. Yet still, despite its empirical failings, "The Population Bomb" was in many ways a great success. By convincing its many readers that ignoring the environment was a perilous course, the book advanced the cause of green activism and set the stage for the landmark environmental legislation of the Nixon era.

It seems particularly appropriate that in this year of rising commodity prices, exactly 40 years after "The Population Bomb," Paul Ehrlich is back. Together with his wife Anne, he has written "The Dominant Animal" (Island Press, 428 pages $35), a book that is being billed as a new and vital environmental warning from the once consummate Cassandra.

Luckily, the book is better than its publicity. Paul Ehrlich is a distinguished entomologist, an expert on lepidoptera. The book's first 200 pages provide a well-written presentation of evolutionary science that shows the depths of Mr. Ehrlich's knowledge. Co-evolution is taught through the poisonous monarch butterfly and its mimic, the viceroy. Geographic speciation is explained with hermit thrushes. The Ehrlichs' description of island equilibria is particularly compelling.

Stripped of the Ehrlichs' political agenda, the book could have been a very nice piece of popular science on the rise of mankind to world dominance. Of course, from Thomas Huxley to Richard Dawkins, evolution has long attracted some of the finest popular science writers. And there was no guarantee that a new book on evolution would survive in the highly competitive world of Darwinian literature.

Perhaps as a result, "The Dominant Species" goes beyond its evolutionary origins. The second part of the book once again sounds the environmental tocsin. I found this part of the book unobjectionable, but the warnings are hardly as exciting today as they were 40 years ago. Enough books on environmental doom have been printed to kill off a forest of giant redwoods. Moreover, the Ehrlichs are no longer making exciting, if irresponsible, claims about the imminent demise of millions. Instead, their more moderate warnings have become the conventional wisdom.

Most of my Republican friends would now agree with the Ehrlichs' view that climate change is a real danger, and that people do not internalize the full environmental costs of producing toxic chemicals and driving. Today, we need sound policies that will make us better stewards of our "natural capital," as the Ehrlichs call it, more than we need more alarms.

Unfortunately, the authors' forays into policy making are the most painful part of the book. The authors have thrown together a left-wing wish list crammed with proposals that stray far from their science. How can environmental issues get better treatment in America? The Ehrlichs propose we "stop gerrymandering." Ah yes. The best thing to save the spotted owl would be to spend millions of hours trying to pass a constitutional amendment that would prevent legislatures, which seem likely to be overwhelmingly Democratic after the next census, from redrawing the political map.

On foreign policy, they recommend that "congress should insist in the short term that the executive branch work with Russia on what may be the most crucial environmental problem of all — the threat of a humanly and ecologically catastrophic nuclear war." Is it really wise, or constitutional, for Congress to pass a resolution that forces the hand of the executive branch in conducting diplomacy? Such a resolution would do wonders to ensure that the State department has as little bargaining power as possible in its dealings with Russia.

The authors are particularly ardent in their opposition to population growth. It is true, as they point out, that there are environmental costs of having more people — all of us use natural resources and energy and bear some responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions. But there are also benefits, especially to the people being born. Each new person has a brain that might come up with new technologies that could reduce humanity's environmental impact. As an urban economist, my life's research has focused on the many ways in which we are all enriched by the people around us. Are there many parents who think that the world would have been better off if they had decided to have one less child?

The Ehrlichs are right that we face real environmental threats, but there are better and worse ways of facing those threats. Today, we need sophisticated policies that weigh costs and benefits, not more warnings. Ironically, the very success of environmental alarmism has convinced many of us that the environment is too important to be left to the environmentalists.

Mr. Glaeser is the Glimp Professor of Economics at Harvard, director of the Taubman Center for State and Local Government, and a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute. -

Seasonality is a boring word. Many environmentalists are now talking about it saying that in a world of high energy prices that trucking berries and other fruits from distant farmers to urban consumers will rise in price and that these urban consumers will respond by eating a more seasonal diet. High energy prices will encourage eating "locally".

This New York Times article turns this logic around. In a nutshell, it argues that South Florida used to be a seasonal place. Nobody wanted to be there in summer (too hot and humid) while everyone wanted to be there in Winter.

Air conditioning and global tourism (fueled by cheap air travel) have transformed southern florida into a year round place. At the end of the article, the global tourism point is fleshed out. British tourists love the fact that Southern Florida is warm and sunny. South American tourists view it as "cool" relative to their home climate and given that their seasons are flipped they want to be there during their "winter" (our summer).

This article has some nice economics detailing how a real estate owner makes substitution decisions when the price of renting her unit varies so sharply over the course of a year. I don't see much behavioral economics here.

New York Times

July 18, 2008

At Home in the Florida Sizzle

By CHARLES PASSY

DENNIS ROONEY can tell you all about the lazy joys of a sticky Florida summer. The beaches that beckon with water temperatures in the nearly bathlike 80s. The roads that are suddenly traffic-free. Even the sight of those tropical afternoon thunderstorms, which constitute a kind of nature-as-theater.

But as it turns out, the real joy of a Florida summer may come in the winter. Because Mr. Rooney chooses to vacation in his two-bedroom home in Delray Beach during July and August, he’s free to rent it out in the prime winter stretch.

“The going rate is four grand a month,” said Mr. Rooney, a Manhattan writer and audio producer. He adds that the winter income “pretty much” covers his year-round costs for the home, including mortgage and maintenance.

But Mr. Rooney’s story is hardly an isolated one in South Florida, long known as a haven for winter seasonal residents (a k a snowbirds) seeking escape from the northern cold. As owners of vacation homes face the financial realities of having that special South Florida getaway, they’re often making something of a devil’s deal. That is, they spend portions of the summer in the state, when it’s at its most hellishly hot and humid (and hurricane prone). In return, they’re fully able to realize the potential for rental income in the blissfully mild winter.

Then again, it’s not strictly about the money. Some appreciate the fact that summer is a decidedly quieter time in South Florida, as evidenced not only by the lack of congestion on the highways, but also by the fact that you can garner a table at some of the most popular restaurants without so much as a reservation.

Plus, some folks just like it hot.

“We have the reputation of staying out from sunrise to sunset,” said Marilyn Horton, a semiretired educator who has a vacation home with her husband, Jim, in Fort Myers Beach. The couple, whose other home is in Niantic, Conn., spend a few weeks every year there in the off-season, dividing the daylight hours between the pool at their gulf-front condo building and the beach.

The Hortons also visit in the winter, but they recognize a certain supply-and-demand business aspect to vacation-home ownership. They’re careful to leave the peak period, from February to mid-April, open for renters.

The reason is that they are often able to more than double the rent for the unit in the winter — $1,400 a week versus $575 to $850 for the occasional summer rentals they book. But just as important, they don’t have to scurry to find tenants in the high season. The rental business comes almost automatically to them, particularly through the Web site WeNeedaVacation.com, on which the couple advertises their property.

“We get hundreds of inquiries,” said Mr. Horton, also a semiretired teacher.

To be sure, such strategizing isn’t entirely new to vacation-home owners in South Florida. And the concept isn’t limited to just that part of the country. In ski areas in New England and Colorado, there are more than a few owners who try a similar approach, staying in the mountains in the summer — they’re just as beautiful without snow — and leaving the skiing to their high-paying tenants in the winter.

But there are factors that have made South Florida particularly suitable for this going-against-the-grain way of viewing vacation-home ownership.

FIRST and foremost, the dynamic of many South Florida vacation communities has changed, with the concept of high and low seasons starting to blur. A half-century ago, Miami Beach all but rolled up its sidewalks at the end of April. Now, those same streets are alive with late-night revelers throughout the summer, since the South Beach clubs pay little heed to the calendar.

Miami Beach “is an all-year playground,” said Laura Adler, a real estate agent who splits her time between South Florida and Aspen, Colo., catering to vacation-home buyers in each.

Much the same thinking extends to the Palm Beach area, where theaters that used to stay quiet during the warm-weather months now keep busy year-round, and the Florida Keys, where a huge fishing community settles in during the summer, taking advantage of the calmer waters.

A result is that property owners need not feel they are being cheated by visiting in the summer. At the same time, they’re still able to take advantage of the fact that winter is the most desirable period, so they can sharply raise their rental rates.

On top of that, South Florida is seeing a growing number of foreign buyers, who often view the summer as the true peak season. In the case of South Americans, that’s because our summer is their winter — they come to escape the cold (or, at least, the cooler) temperatures right when many South Floridians are wishing they could escape the heat. And Europeans, particularly Britons, simply take a more benign view of the summer, perhaps because they’re contending with damp, rainy weather for much of the rest of the year.

“I’ve never once run into a European who said it’s too hot,” said Paul McRae, president and broker at the Fort Lauderdale-based Galleria Collection of Fine Homes, which handles all sales for the Trump International Hotel & Tower in Fort Lauderdale. The condo hotel has 298 guest rooms, with the remaining units starting around $700,000, and is set to open early next year. Mr. McRae estimates that more than 50 percent of his buyers are looking primarily at summer use.

Which brings up another factor behind the summer boom: the rise in condo hotels throughout South Florida in the last decade. After all, this form of property ownership, in which a buyer buys a hotel unit and then lets the hotel rent it out in exchange for the hotel’s taking a cut of the receipts, is built around the idea of building rental income to defray the owners’ costs. So it is only natural that those who buy units, which they can readily use at any time, would be hesitant to grab the prime winter dates for themselves. At the Trump International Beach Resort in Sunny Isles Beach, between Fort Lauderdale and Miami Beach, a two-bedroom unit can go for close to $1,200 a night in February.

OF course, the concept of maximizing rental income does not apply only to condo hotels. As South Florida experienced a huge rise in values of all kinds of housing, from roughly 2000 to 2005, it became a speculators’ market. And those speculators are now eager to get the highest possible rental receipts, since they are planning to hold on to their properties only until the market rebounds and they can make a profit.

Others who use their Florida homes only in the summer include people who have bought homes for their later retirement years. “If it’s something they’re buying for future use, the goal is to cover as much of the expenses as they can,” said Kathy Jones, Florida coordinator for WeNeedaVacation.com.

The same applies in the case of a home that’s been inherited. Martha MacPherson, who works in software sales in Boston, takes as much advantage as she can of a Marco Island home passed down to her and her sister from her mother. But since Ms. MacPherson is really thinking ahead to retirement, she’s now renting out the home in the winter as a financial necessity.

“The place is paid for, but you’ve got condo fees,” she said.

Still, those who rent out their units in the winter aren’t necessarily deprived of the occasional in-season vacation. The key is being flexible.

That is how Linda Spencer, a Deerfield, Mass., pottery designer, approaches vacation-home ownership. She has three properties throughout the Florida Keys. If her rental business is strong, she stays ensconced in New England. If there’s an opening on the calendar, she’ll grab it, regardless of whether it’s summer or winter.

In fact, she prefers summer in the Keys, particularly for the great boating and snorkeling opportunities it affords. “I wouldn’t be hanging out that long in the water during the winter,” she said.

But what about the brutal heat and humidity?

As far as Ms. Spencer is concerned, it’s hot almost anywhere you go in the summer.

“It was just 101 degrees in Cape Cod,” she said, “and people there don’t have air-conditioning.” -

While I won't win a Clark Medal and the monthly IDEAS email tells me that I have barely cracked the top 5% of academic economists, I have now achieved something that I'm proud of. How many Chicago Economists can say that their work is profiled on the front page of the City of Berkeley's Webpage? I'm waiting for Becker, Glaeser, and Heckman to join me there in the rare air.

Is the Berkeley City Hall talking about my AER piece from 2007 or my 2006 Green Cities book or my 2008 Heroes and Cowards book? Or perhaps my Fall 2007 Readers Digest piece?

No, the buzz is about this;

Working Papers

2008-19, Green Market Geography: The Spatial Clustering of Hybrid Vehicle and LEED Registered Buildings, Matthew E. Kahn and Ryan K. Vaughn

www.zimancenter.com/research_working_papers.html -

I've always wondered what the price of gasoline would have to be for Harvard to start drilling in Harvard Square. Now, I'm not a geologist and I don't play one on TV but there could be some oil deposits under that Burger joint. More seriously, when do high commodity prices lead to radical changes in land use patterns?

Fun Blog Reading from The Economist . The full draft of the Glaeser/Kahn paper should be released as NBER Working Paper in a couple of weeks. -

Housing will soon be a pinch more affordable around the country. For reasons perhaps related to humidity and housing supply regulation, Houston is an affordable city for the middle class seeking out the American Dream. In this editorial, Ed Glaeser contrasts New York City and Houston. If I'm reading this article correctly, it appears that Rice University should make Ed an offer. Ed Glaeser Celebrates Houston

-

I was just walking my son to school within .25 miles of UCLA and a tall woman with a friendly dog walked past us. Upon second glance, I convinced myself that it was tennis great Venus Williams . She is taller than I am and appears to be in better shape.

While the Arts Section of the New York Times rarely interests me, this piece is worth reading.

In a nutshell, when wealthy people go on cruise ship vacations they over-bid for art in auctions held on the ship. How would you explain this fact?

1. absence of information --- bidders are unable to easily access google to lookup the market price of a specific piece of art such as a Picasso doodle and without this info the winner's curse kicks in.

2. non-separable preferences --- when you are relaxed on a cruise, you view yourself as a "big spender" who deserves the best things in life. as you let your guard down, you over-bid for junk that you would never bid on if you were on land in the middle of your normal life.

#1 is a weird explanation because if you know that you do not know the value of a commodity that you are bidding on then this should lead you to shave down your bid because you know that ex-post that you will be a "victim" of over-paying (if you win the bidding).

#2 is also weird because you should be aware that a piece of Art is a durable and you will be stuck with it when you get off the cruise. #2 would be a better explanation for consuming a fancy bottle of wine or rare lobster while on the cruise. But again, a perosn with mature preferences should be aware that even if their passions are stirred up while on the cruise that the cruise will end and they will revert to being their "old self" who doesn't want a $50,000 Picaso.

So, my point is that cruise ships offer economists an interesting lab for testing behavioral models. When people are relaxed do they make very different choices? Dan

Ariely suggests that when men are in a state of "arousal" that they make weird choices. I'm saying that this cruise ship is running the opposite experiment. -

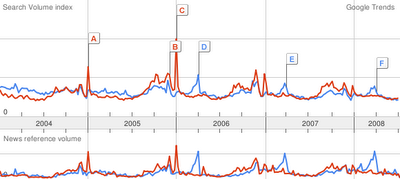

UCLA is the blue line and USC is the red line. Google is ranking these two schools as roughly equal in terms of "buzz". How much of this traffic is generated due to college sports versus college economics?

http://www.google.com/trends?q=ucla%2C+usc&ctab=0&geo=all&date=all&sort=0

The "eruptions" on the graph take place when big sports contests take place such as the Rose Bowl. -

Exciting things are taking place at the UCLA Institute of the Environment. If the existence of a webpage is any sign, we now have an active New Research Center at UCLA focused on Corporate Environmentalism . What will this research center actually do?

Suppose that you work at a company located somewhere in Southern California (i.e metro Los Angeles). Your company might be wondering how AB32 Climate Change legislation will affect your company's profitability? or what new business opportunities California's climate change regulation might offer? Your company may sell products with green features such as LEED certified buildings or organic toothpicks (I'm kidding about this one). Alternatively, pollution may be a byproduct of your cement plant's production process.

We want to be talking to such firms and offering some cheap advice. Why do we want to talk? What is our stake? To quote a Sprite commercial; "what is our motivation?" My environmental economics class has over 100 students right now. I bet that it would have 200 if I uncapped enrollment. Many of my students are fascinated by free market environmentalism. They want to work for firms that are making money and are exciting and are "green". We need to identify business partners seeking smart, ambitious students to work for them.

My own motivation is that I want to learn more about how "real" businesses actually operate and make decisions that have environmental consequences. As I get to know these firms and as they get to know me, I'm hoping that they would trust me to share their data with me and perhaps be willing to run some experiments to learn about what works and what doesn't work in day to day operations. For example, what research have they done in terms of marketing plans and cost analysis in determining whether "green" varieties of their products truly offer profit opportunities? Have they run formal experiments to measure whether their consumers are willing to pay a price premium for green products? Consumers may say that they are willing to in feel good surveys but when they actually face a market choice do they "vote with their wallet"?

What will our Center do in the short run? We are arranging for business leaders to visit our Institute of the Environment to give presentations on what they are doing and what challenges they face in implementing their "green" business plans. Such presentations allow us to learn about such firms and introduce our students to such firms. Los Angeles is a diverse big city and UCLA needs to raise its intellectual profile. I get the sense that people think UCLA = basketball and USC = football. This simple formula vastly undersells both schools.

In the short run, I'm getting ready to go to the NBER Summer Institue next week and then to spend a few weeks in Berkeley, California. The Summer Institute is a good opportunity to remember Boston humidity and to hear some interesting environmental and real estate papers. I'm looking forward to seeing old friends and to work with some of my co-authors. Will it rekindle my love of Boston? I doubt it. I worked at Harvard for 2 years and at Tufts for 6 years. My 8 years in or close to the 02138 zip code were enough for now. California is the place to be. The Internet offers access to the ideas being generated in Cambridge.

Berkeley features my favorite in-laws who are eager to see their grandson. In August, I'll need to clean up a couple of "revise and resubmits" for good journals and get some papers ready for journals. I also have a big think project that I'm not ready to show to my blog readers yet. Just think of it as a poor man's Freakonomics for the greens. Think of Paul Ehrlich meets Milton Friedman in a wrestling cage match.